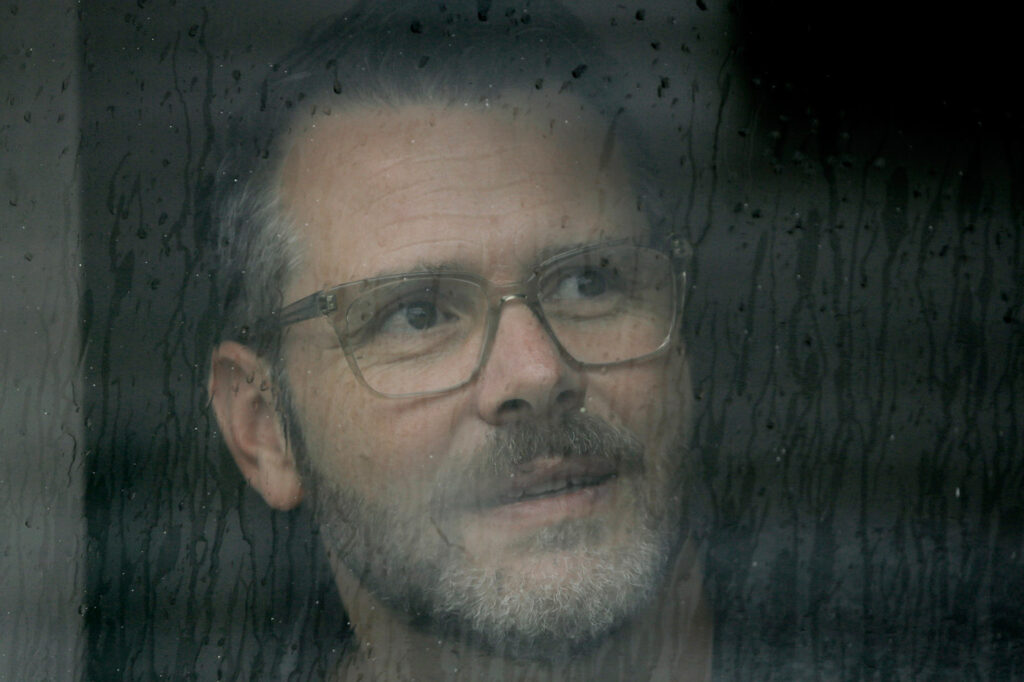

The Floret—Ernst Hupel

November 18, 2019

“It was a personal investment.”

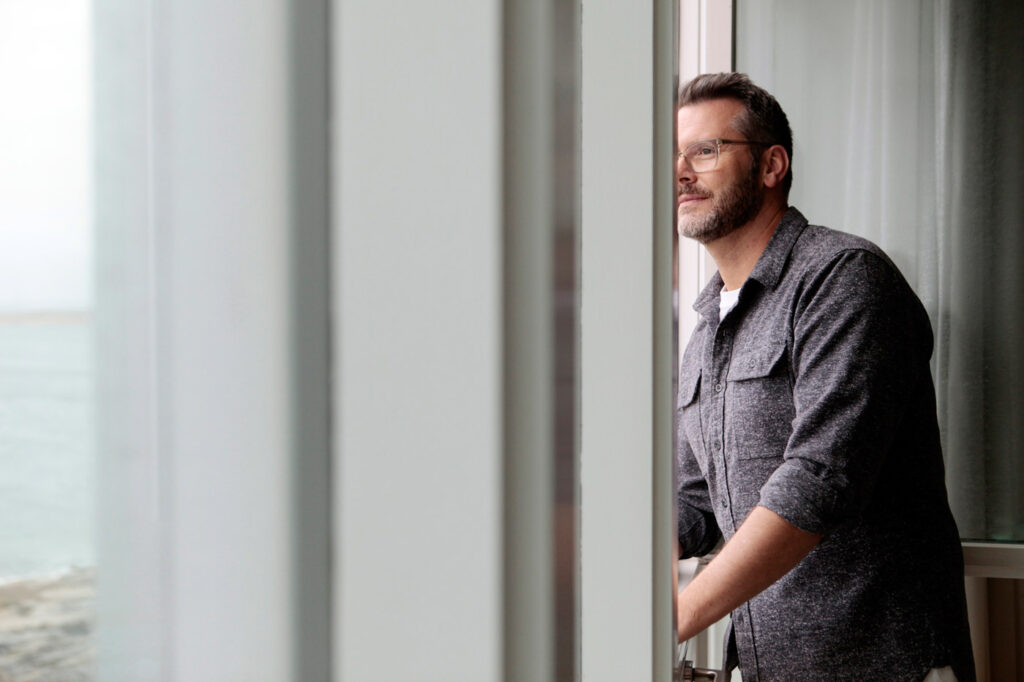

The roads of Fogo Island are empty this morning. The weather forecast is calling for high winds and 50 millimeters of rain: a daunting amount of precipitation even for seasoned coastal dwellers. The drive to Fogo Island Inn is accompanied by the kind of wind that cuts across, under, and around a vehicle, rocking it in a way that unnerves the uninitiated but goes nearly unnoticed to those who frequent these routes. The staff at Fogo Island Inn are talking about getting a guy named Noah on the phone… “we might need an ark,” they joke.