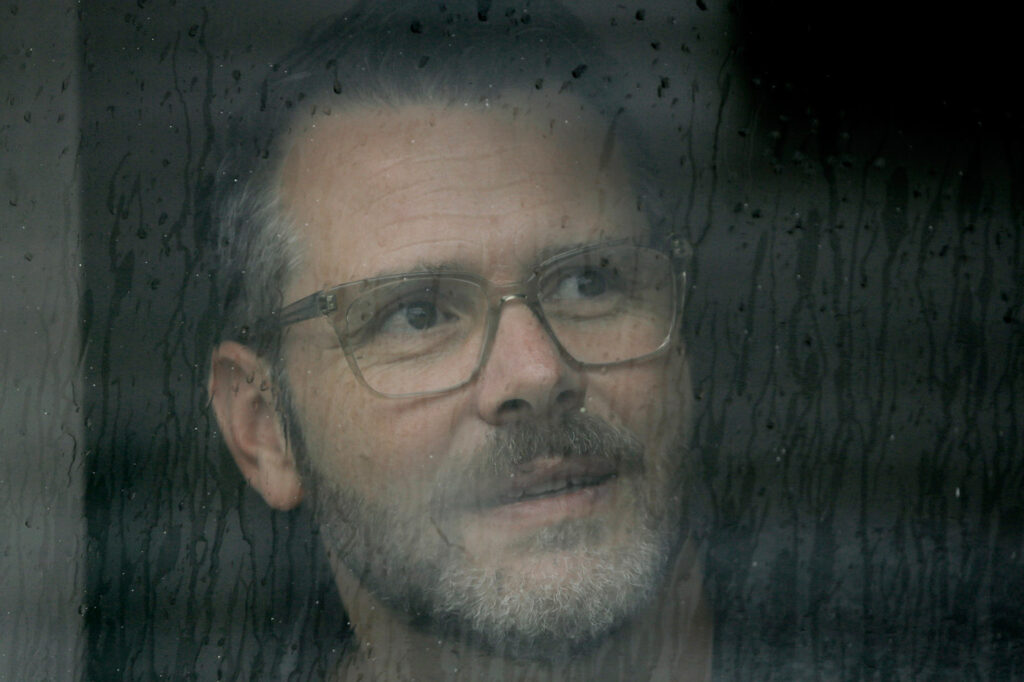

“Every day is an opportunity to learn something new,” PJ Decker observes as we sit down to our first cup of tea at the kitchen table of the restored Punt Premises. Of the four traditional outport structures that comprise the Premises, the kitchen is the only room with some modern appliances—an appreciated touch when hosting youth and adult programming on site. Outside the sun is obscured by cloud cover and it’s what would be considered a “mauzy” day in Newfoundland parlance. For the past few weeks Decker has been preparing every detail of the Premises from the mounting of cultural artifacts on the wall to re-corking the fleet of punts that will soon bob within the harbour of Joe Batt’s Arm anchored by a technique affectionately referred to as ‘Punts on a collar.’ The 2022 Punt Premises season kicked off on June 1st and PJ is our new Punt Master. (While the role is new, PJ is no stranger to Shorefast; he has worked in various capacities over the years including maintenance and as an outdoor adventure guide.)

“Spudgel, for example,” PJ continues, “is a term I learned just yesterday from my dad.” His dad, Pete Decker, is a former fisher and trusted advisor to Shorefast’s work around the punts; he stops by the Premises regularly. Born in 1949—the year Newfoundland joined Canada—Pete is of the last generation that grew up when many of the traditional fishing tools and boatbuilding techniques of the inshore fishery were still in practice. With memory to draw on, Pete is quick to provide illuminating anecdotes to this former way of life and it is clear that his first-hand knowledge and the contextual history of the fishery has been an integral part of PJ’s own upbringing.

“My dad loved to be in the company of his father and uncles, all of whom were fishers, and to learn everything he could about fish, stories, and the sea. And I’m the same way. For me, the Punt Premises is where I belong. Punts and stages and coves—that’s what I’ve done all my life. Walking, wading, and exploring the shoreline.”

PJ’s new role as Punt Master is both an extension of the informal education that weaves its way from generation to generation, and a concerted effort to bridge relevant aspects of Fogo Island’s history into the future.

The spudgel, as it turns out, is a wooden dipper connected to a long handle. It was a tool used to scoop cod liver oil from the barrel it was housed in (the two main by-products of harvested cod at the time were salt-cod and cold liver oil). In each of the structures that comprise the Premises—a traditional fishing stage, two fishing stores, and a saltbox-style house—various curiosities related to outport culture are mounted with labels identifying their purpose.

Walking through each interior reveals the particulars of every-day-life where some of the most impressive tools are simple design hacks: on a rack meant to carry dried cod the handles have been deliberately carved to arc upwards so that your knuckles don’t get crushed when you place the rack on the ground. At every juncture there is a thoughtful and deliberate attempt to make processes smoother, more efficient. It calls to mind a quote attributed to the author John Durham Peters, “Gathered in a single clock, knife, or shoe are many lifetimes of practical knowledge.” Continuing through the Premises serves as a fascinating reminder that beyond all the inventive tools and process to aid life and work, fishers also had to employ numerous intangible skills including the capacity to navigate by landmark, to read ocean currents, to predict the weather and understand the proclivities of fish. Both hand-crafted instruments and experience born of repetition and intuition were essential for surviving and thriving.

Equally fascinating is the fact that none of this would exist were it not for the proliferation of cod and marine life in this distinct region of the Atlantic Ocean (Fogo Island is in the pathway of the Labrador current colloquially known as “the lungs of the planet”). It was the mighty cod alone that begot an entire industry that encouraged people to settle in a place that required incredible perseverance.

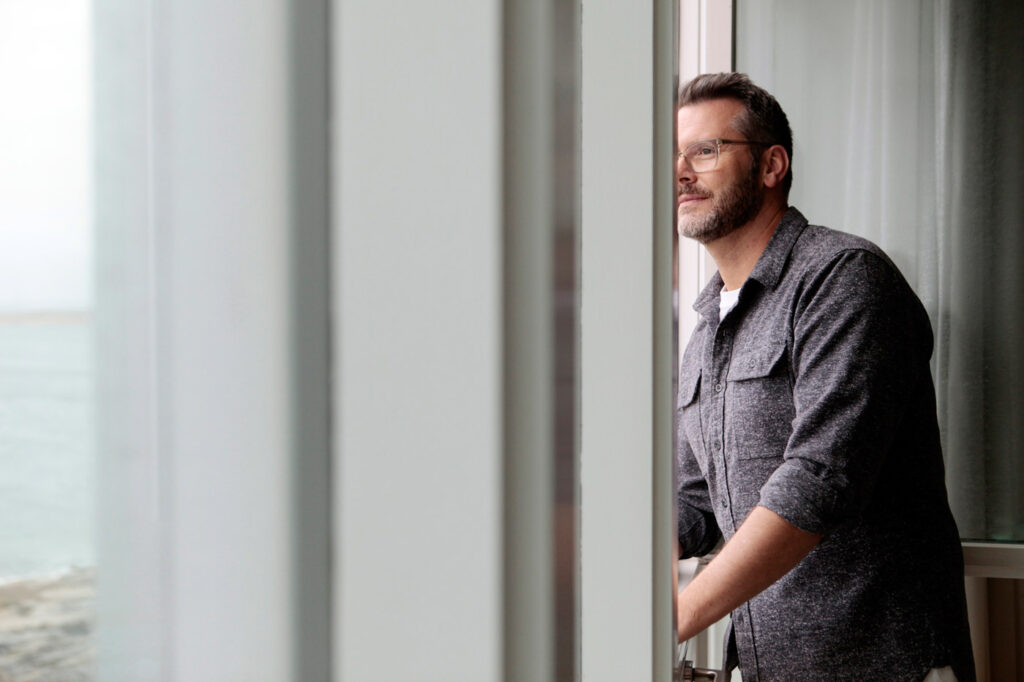

Today, whether you continue to make your livelihood on the water or not, the sea is inextricably linked to the experience of living on Fogo Island.

“The sound of my childhood,” PJ notes, “was the constant thudding of my dad corking the seams of his boat.” It’s a happy memory of course—this constant background music, a comforting thrum that belies a childhood near water and the rhythms of methodical, predictable days. Working with the punts at the premises, PJ reflects on the effort it takes to prepare them for the ocean: He’s been patiently filling each punt with water for a few days, allowing the wood to swell and naturally eliminate any open seams. The traditional process of corking a punt boat – creating a seal between the wood planks—could involve any number of tools but most often came down to the caulking iron (viewable at the Premises) and a hemp-like material called oakem that was malleable enough to fit in between the wood and effectively repel water.

“It’s quite likely that the sound my dad would associate with his own childhood would be entirely similar to the constant thudding I associate with mine.” It is hard to imagine this not being true; Pete’s father and uncles would have spent considerable time repairing their wooden punts. The sheer force of the Atlantic Ocean hasn’t altered with time, and boats, no matter if they are wood or fibreglass, will always require maintenance.

While the fishing industry continues to be the most important business on the Island (centered around the Fogo Island Co-operative Society Ltd.)—notably as Fogo Island’s first locally-owned asset and the driver behind the Island’s resurgence after industrial trawlers depleted the cod stocks—creating a bright future depends on developing complimentary economic engines alongside that crucial pillar. Shorefast’s work is about enabling that diversity, so that people, especially young people who are often the first to migrate, have the option to stay and build the life they want. “At the time of my graduation in 2001 there was very little you could do on the island unless you were involved in the fishing industry. Now, all my siblings and I have been able to return home to jobs that previously didn’t exist.”

Before Shorefast commissioned boat-builders to craft new Punts, there were very few of the vessels left and knowledge of the traditional way of life—the harvesting techniques, the boats, the various tools and ways in which merchants and fishers would interact—was little known for community members PJ’s age and younger.

“When speaking with my friends I’m often surprised that they don’t know all of these details,” PJ offers as a way to explain the relevance of the Premises to the Fogo Island community today. This information is new to a lot of people and it’s an opportunity to re-evaluate the ingenuity of Fogo Islanders as they eked out a life in a remote location that by all measures resists easy living. Anyone that lives on Fogo Island or spends time on Fogo Island will instantly recognize the immense impact weather plays on daily life; precarity and adaption have been essential tools for survival on the edge of the northeastern Atlantic.

“How we continue to be shaped by that experience even as we evolve to be a modern outport is valuable and worth holding onto.”

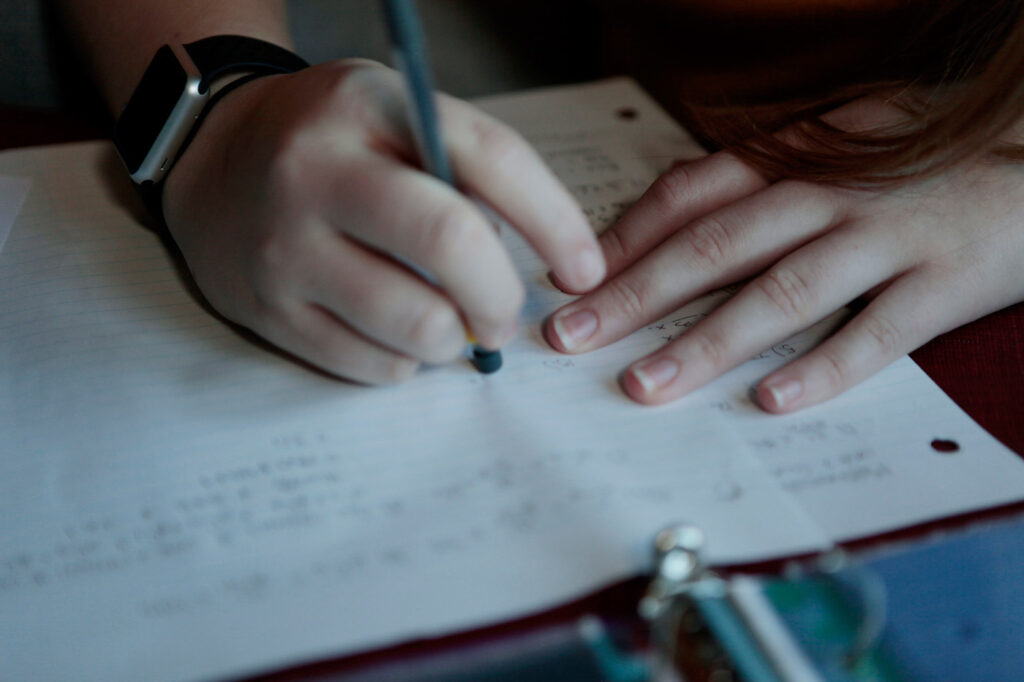

The Punt Premises celebrates all facets of life that surrounded the inshore fishery, including the artisan craft traditions that supplied household textiles and cooking practices, much of which can be explored through interactive programming hosted on site. In this way the Premises has never been a static space purely for reflection; it is also a facility for community engagement and the 2022 season marks a dedicated expansion of its programming.

“With few community hubs on the island, we see the Premises as an opportunity to provide the kind of hands-on programming that kids and their parents are hungry for.” The Punt Premises will gear activation events around environmental stewardship and conservation efforts for kids and adults, as well as cultural programming focused on knowledge preservation.

With easy access to the shoreline there is lots of potential for learning, especially for kids. Simply observing the shallow waters below the fishing stage alone is an exercise in seaweed and fish species identification (hint: look for the eel grass). Tying simple and informative training modules into interactive kid-friendly programming will be an important part of Fogo Island’s adaptive future as coastal communities continue to face the brunt of the climate crisis. Building a modern outport community depends on nurturing leadership and knowledge that is based on the specificity of this place.

PJ attributes a large part of this understanding to the exchange between visitors from away and those who live on Fogo Island. Fogo Island Inn’s emphasis on regenerative tourism means that decisions about how the hospitality sector grows on Fogo Island are rooted in sustainable approaches to the environment and set to a scale that allows people to engage meaningfully with one another. “To see how many people are interested in what we have to offer is a big shift in the way we think of our past, especially as we imagine the future we want to create.”

Thinking back to his own childhood in the 80s, PJ recalls what is likely universal for any kid growing up near an ocean that continues to be both temperamental and life-giving: “When our fathers would return to the harbour after a day at sea, all us kids would run over to the rocks and watch in awe as they unloaded their fish onto the stage.”

The prolific marine life that encouraged people to settle on Fogo Island and develop an inshore fishery that sustained generations is an integral part of what informs culture to this day, and crucially will inform approaches to ocean sustainability well into the future. The continuum of an outport life that is modern, adaptable, and diverse relies on it.

“For things to remain the same, things will have to change,” the adage dictates.

PJ’s work at the Punt Premises embodies this notion. What we carry with us is important.